As a public school teacher for sixteen years, I sometimes feel like I’ve seen it all.

I’ve seen Standards come and go (and despite the brouhaha about Common Core, it’s really not that different than anything that’s come before). I’ve seen standards come and go (I have hope that they’re starting to come back).

I’ve seen parental attitudes change from, “I cannot believe my kid did that! There will be major consequences at home!” to “You’re targeting my child”/”He was only doing what every other kid does and gets away with”/”Your course is too challenging for my child”/”Your course doesn’t challenge my child”/”School problems stay at school”/all the excuses.

I’ve worked with caring, inspiring, passionate, gifted teachers and administrators. I have worked with administrators and teachers that undoubtedly should have chosen a different profession. I have been bullied so badly by an administrator and two teachers in a district I once worked in that I developed PTSD related to being raped as a college student and the abuse I suffered at the hands of my ex-husband. I have worked with administrators, faculty, paraprofessionals, secretaries, custodians, and lunch ladies that have gone out of their way for me, and I have tried to always go out of my way for my colleagues.

I have loved each and every student that has been in my classroom. I love them unconditionally, accepting the faults that each carries as I hope that they accept my faults and shortcomings. I taught them reading and writing, and I believe that I taught most of them well. I further believe that I taught them patience, kindness, acceptance, manners, and, yes, respect.

One of the reasons that teaching has never been dull for me is that I take the time to get to know my students. I try to connect with them quickly and strongly. They are people, after all, and if we can connect over dogs or movies or music right away, if they know that I remember (and care) when their birthdays are or that they, like me, have lost a parent, that I struggle with ADHD, that it always hurt me that my sister is “the smart one” in the family, the end result is that they know I care about them. They matter to me and they know it, so if it matters to me if they know how to use commas or use good evidence to support their argumentative essay or analyze the responsibilities of friendship in Of Mice and Men, they have a solid history of rising to the occasion.

I would go to the mat for my students, and they know it; however, I also have high expectations for them, as students and as people, and they know that as well. I have never pigeonholed them by socioeconomics, or race, or sexual orientation, or gender. I have not altered my expectations for them.

This is important, so if you’re just skimming this long piece, please read this part closely: I used to tell myself that I was colorblind, that I treated the black kids, white kids, gay kids, poor kids, rich kids exactly the same.

It’s even possible that I did.

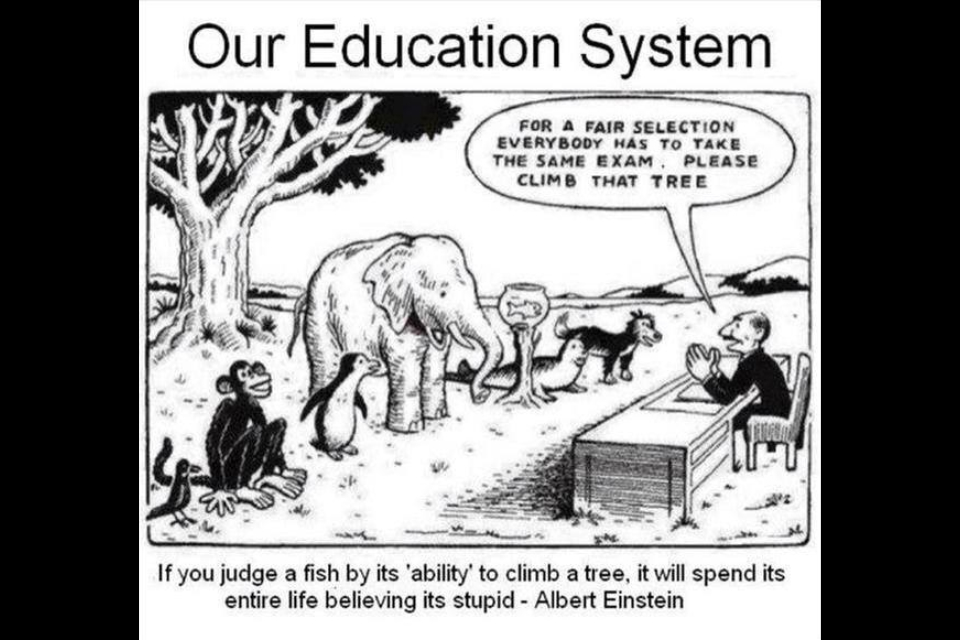

But how many of us have seen this comic?

The gist of it is that some people are simply born well-equipped to succeed very easily in our educational system, and some are born doomed from the start.

I hate this comic.

I hate it because it makes it about the test … and it should always be about the students.

All children come to the educational table with strengths and weaknesses. There have been educational philosophies intended to bolster the one and ignore the other. There have been movements to teach “Executive Functioning Skills” to all, when the students that need them are going to need far more than a cookie cutter weekly lesson on notetaking to truly develop any substantive results and those that already possess strong notetaking skills still have to sit through the lessons because “reinforcement won’t hurt them”.

Students bring their life experiences--the good, the bad, and the ugly--into the classroom with them. Skin color, sexual orientation, gender identification, which end of town you hail from … those are key parts to who a student is. Ignoring that fact is a grave disservice to not just students but people in general. As an approaching-middle age white woman raised in an affluent family, how can I presume to understand what it feels like to be anything else?

And haven’t my life experiences shaped who I am and the decisions I make? Am I like any other other approaching-middle age white woman raised in an affluent family? Of course I’m not. I was seven months pregnant at my high school graduation. I drank heavily in college. I was raped by an acquaintance. I was hospitalized for a month with pancreatitis in my twenties and for a month with post-surgical complications when I was forty. I have lost a parent. I suffered horrible abuse from my abusive alcoholic/addict ex-husband. Would anybody know those things about me by looking at me? I repeat, though, haven’t they shaped who I am? Would pretending they never happened be doing me any favors?

I heard a colleague become very angry at a recent training intended to drive home the idea that it is doing kids a disservice to say, “I don’t see Bobby as a black kid. I just see Bobby as a kid” or “I don’t see my cousin as a lesbian. I just see her as a person.” “I’m colorblind!” she said over and over. With that mindset, we are taking away a huge part of the experiences people have had as a result of the hand they were dealt.Teachers cannot even begin to tap into the difference we can make to children if we refuse to see their colors, their shapes, the fact that they work a full-time job to help their mother pay rent.

I’m pretty sure this colleague is in the minority, but it is a vocal minority.

Teachers that take the time to know their students--and I believe that most of us truly do--will take into account the many and varied experiences, good as well as bad, that each child has experienced. To do otherwise is to do a disservice.

We look at where they are at when they come to us, and we do everything in our power to push them ever higher. We show them pathways, we encourage them, we are open and honest with them when we think they are making a mistake, and they will and do listen to us.

Sometimes, though, they ignore us. This is true of students from all races, creeds, sexual orientations, socioeconomic statuses, mental illness, addicts/alcoholics, and so on.

Sometimes, no matter how much we care, no matter how much we try, teachers can only do so much.

And here is the elephant in the room, the elephant that nobody wants to talk about, the elephant that frightens me terribly even as I write this. I am, after all, a public school teacher that loves her job, and I do not want to be squashed by that elephant.

I think my point can best be made with an anecdote.

My first teaching job was at a middle school in a large city. I had a minority student, “Victor”, in my Honors class. He was a strong student and an incredibly nice kid, the kind of kid that would stop and help you if you dropped a huge jar of M+Ms in a busy hallway. Victor was a straight A student across the board, and he could have pursued and excelled in any career path he wanted.

Increasingly, Victor came to school with bumps and bruises. Once, he had a tooth knocked out. Because I was young and idealistic--and most of all “colorblind”--I pulled Victor aside and asked what was going on. “Just some guys giving me grief,” he said, cheerfully enough. “It’s no big deal.” I wasn’t so sure about that, but Guidance told me that it’s a common occurrence and, if it happens off of school ground, there is nothing they can do.

I thought they meant fighting and tried to forget it.

One day, I was leaving work and Victor was sitting on the sidewalk in tears, his vandalized and unrideable bicycle next to him. I ran over to him, and he quickly stood up and wiped the tears from his face.

“I’m fine, Mrs. L,” he said.

“What can I do to help you?” I asked. “Do you want a ride? Do you want me to bring your bike to a repair shop? I’ll pay to get it fixed, Victor. This is horrible. We need to call the police.”

Victor looked stricken at that. “Please, Mrs. L, just leave me alone.”

“But … why, Victor? You are such a nice kid, such a smart kid, why would anyone do this to your bike? Why would they beat you up?”

“You really don’t know, do you?”

Almost in tears myself (please remember, I was twenty-four at the time), I shook my head.

“They used to be my friends, but now they don’t like it that I do well in school. They keep saying I decided to ‘go white’.”

“‘Go white’? I don’t understand.”

“In my neighborhood, in my family, we don’t take honors classes and get straight As and awards from principals. We stick together. We don’t try to be better than what we are.”

“But … you’re a straight A student in Honors classes. You can do anything you want, Victor.”

“I know,” he said with a sunny smile. “That’s why I don’t let this stuff bother me.”

The next day, Victor was not in school. He had been badly beaten for talking to a white teacher outside of school. He came back to school a few days later, determined as ever to break the mold. I left the district to take a job closer to home, but I remember thinking that Victor would be okay; he would be a success story.

I returned to that district at the high school level two years later, missing the size and the diversity and the unique challenges that I loved working with.

I saw Victor once, in a crowd of students in the same minority group as he. He saw me, did a double take, then looked away. Confused, I went on my way. I did ask around, though. Victor was a D/F student in low level classes. He was involved in gang activities. Rumor had it he’d been in police trouble on several occasions. He was no longer “a nice kid”.

I have no idea what happened to Victor, the story that transpired in the years I worked in a different district. I do know that he changed dramatically, that he had clearly made the decision that ‘going white’ was no longer his path.

It was not the school staff that did this to Victor, nor was it necessarily his family. Victor had, somewhere along the way, lost the strength to stand up to his peer group. He had accepted his peer-defined identity of who he should be as a minority, and that identity did not value Honors or AP classes, never mind school itself.

Nobody wants to talk about the power of peers when it comes to minority groups possessing an “Us versus Them” paradigm, but that is the very base of it. I say that from fifteen years in education.

It is the elephant that nobody wants to name because we fear being labeled racist even as we squawk about being colorblind.

I take each child that I am given the privilege to teach, and I work with them from where they are at on what they are able and willing to give and receive. I truly believe that most teachers do the same.

So why am I writing this today?

The city I live in is in upheaval over student representatives being added to an ad-hoc school board committee tasked with exploring ways to include student voice on the school board. Each high school principal was asked to choose a representative from their school. The principals, I’m sure, worked hard to ensure that these representatives were not white, Harvard-bound males. It is a diverse city, and ignoring that diversity would be wrong. Principals know their student body, and they know the student that would best represent its unique voice.

What has happened is that a group focused on community organizing, a group made up of exclusively of minority students, a group that has made derogatory and false statements about their schools, a group that has misrepresented adult leaders as students to the press, has pushed their way into the ad hoc group made up of the principal-selected representatives.

Among other things, this group has been vocal about minorities being discouraged from (or even forbidden from) taking upper level classes. They blame the schools. They blame the teachers. They blame the school board.

Victor was the most extreme case I’ve seen, but based on my experience as a teacher it is the peer groups that want to keep anyone from defecting, from ‘going white’. The opportunities are there, for minorities and for all students, if they are willing and able to work to achieve them. They are encouraged by teachers. In fact, teachers and school administration would love it if their upper level classes were a perfect balance of diversity. What a feather in the school district’s cap that would be!

But teachers and citizens that are not of this minority group do not want to say anything. They don’t want to name the elephant because “Racist” or “Sexist” or “Prejudiced” is not a label anyone wants to wear. It would be all too easy to dismiss anyone who tries to raise this issue with one of those labels without ever addressing the issue itself.

And that group? They do not want to talk about the elephant in the room either, but perhaps they should if they truly want to engage in a dialogue that leads to understanding.

I’ve seen Standards come and go (and despite the brouhaha about Common Core, it’s really not that different than anything that’s come before). I’ve seen standards come and go (I have hope that they’re starting to come back).

I’ve seen parental attitudes change from, “I cannot believe my kid did that! There will be major consequences at home!” to “You’re targeting my child”/”He was only doing what every other kid does and gets away with”/”Your course is too challenging for my child”/”Your course doesn’t challenge my child”/”School problems stay at school”/all the excuses.

I’ve worked with caring, inspiring, passionate, gifted teachers and administrators. I have worked with administrators and teachers that undoubtedly should have chosen a different profession. I have been bullied so badly by an administrator and two teachers in a district I once worked in that I developed PTSD related to being raped as a college student and the abuse I suffered at the hands of my ex-husband. I have worked with administrators, faculty, paraprofessionals, secretaries, custodians, and lunch ladies that have gone out of their way for me, and I have tried to always go out of my way for my colleagues.

I have loved each and every student that has been in my classroom. I love them unconditionally, accepting the faults that each carries as I hope that they accept my faults and shortcomings. I taught them reading and writing, and I believe that I taught most of them well. I further believe that I taught them patience, kindness, acceptance, manners, and, yes, respect.

One of the reasons that teaching has never been dull for me is that I take the time to get to know my students. I try to connect with them quickly and strongly. They are people, after all, and if we can connect over dogs or movies or music right away, if they know that I remember (and care) when their birthdays are or that they, like me, have lost a parent, that I struggle with ADHD, that it always hurt me that my sister is “the smart one” in the family, the end result is that they know I care about them. They matter to me and they know it, so if it matters to me if they know how to use commas or use good evidence to support their argumentative essay or analyze the responsibilities of friendship in Of Mice and Men, they have a solid history of rising to the occasion.

I would go to the mat for my students, and they know it; however, I also have high expectations for them, as students and as people, and they know that as well. I have never pigeonholed them by socioeconomics, or race, or sexual orientation, or gender. I have not altered my expectations for them.

This is important, so if you’re just skimming this long piece, please read this part closely: I used to tell myself that I was colorblind, that I treated the black kids, white kids, gay kids, poor kids, rich kids exactly the same.

It’s even possible that I did.

But how many of us have seen this comic?

The gist of it is that some people are simply born well-equipped to succeed very easily in our educational system, and some are born doomed from the start.

I hate this comic.

I hate it because it makes it about the test … and it should always be about the students.

All children come to the educational table with strengths and weaknesses. There have been educational philosophies intended to bolster the one and ignore the other. There have been movements to teach “Executive Functioning Skills” to all, when the students that need them are going to need far more than a cookie cutter weekly lesson on notetaking to truly develop any substantive results and those that already possess strong notetaking skills still have to sit through the lessons because “reinforcement won’t hurt them”.

Students bring their life experiences--the good, the bad, and the ugly--into the classroom with them. Skin color, sexual orientation, gender identification, which end of town you hail from … those are key parts to who a student is. Ignoring that fact is a grave disservice to not just students but people in general. As an approaching-middle age white woman raised in an affluent family, how can I presume to understand what it feels like to be anything else?

And haven’t my life experiences shaped who I am and the decisions I make? Am I like any other other approaching-middle age white woman raised in an affluent family? Of course I’m not. I was seven months pregnant at my high school graduation. I drank heavily in college. I was raped by an acquaintance. I was hospitalized for a month with pancreatitis in my twenties and for a month with post-surgical complications when I was forty. I have lost a parent. I suffered horrible abuse from my abusive alcoholic/addict ex-husband. Would anybody know those things about me by looking at me? I repeat, though, haven’t they shaped who I am? Would pretending they never happened be doing me any favors?

I heard a colleague become very angry at a recent training intended to drive home the idea that it is doing kids a disservice to say, “I don’t see Bobby as a black kid. I just see Bobby as a kid” or “I don’t see my cousin as a lesbian. I just see her as a person.” “I’m colorblind!” she said over and over. With that mindset, we are taking away a huge part of the experiences people have had as a result of the hand they were dealt.Teachers cannot even begin to tap into the difference we can make to children if we refuse to see their colors, their shapes, the fact that they work a full-time job to help their mother pay rent.

I’m pretty sure this colleague is in the minority, but it is a vocal minority.

Teachers that take the time to know their students--and I believe that most of us truly do--will take into account the many and varied experiences, good as well as bad, that each child has experienced. To do otherwise is to do a disservice.

We look at where they are at when they come to us, and we do everything in our power to push them ever higher. We show them pathways, we encourage them, we are open and honest with them when we think they are making a mistake, and they will and do listen to us.

Sometimes, though, they ignore us. This is true of students from all races, creeds, sexual orientations, socioeconomic statuses, mental illness, addicts/alcoholics, and so on.

Sometimes, no matter how much we care, no matter how much we try, teachers can only do so much.

And here is the elephant in the room, the elephant that nobody wants to talk about, the elephant that frightens me terribly even as I write this. I am, after all, a public school teacher that loves her job, and I do not want to be squashed by that elephant.

I think my point can best be made with an anecdote.

My first teaching job was at a middle school in a large city. I had a minority student, “Victor”, in my Honors class. He was a strong student and an incredibly nice kid, the kind of kid that would stop and help you if you dropped a huge jar of M+Ms in a busy hallway. Victor was a straight A student across the board, and he could have pursued and excelled in any career path he wanted.

Increasingly, Victor came to school with bumps and bruises. Once, he had a tooth knocked out. Because I was young and idealistic--and most of all “colorblind”--I pulled Victor aside and asked what was going on. “Just some guys giving me grief,” he said, cheerfully enough. “It’s no big deal.” I wasn’t so sure about that, but Guidance told me that it’s a common occurrence and, if it happens off of school ground, there is nothing they can do.

I thought they meant fighting and tried to forget it.

One day, I was leaving work and Victor was sitting on the sidewalk in tears, his vandalized and unrideable bicycle next to him. I ran over to him, and he quickly stood up and wiped the tears from his face.

“I’m fine, Mrs. L,” he said.

“What can I do to help you?” I asked. “Do you want a ride? Do you want me to bring your bike to a repair shop? I’ll pay to get it fixed, Victor. This is horrible. We need to call the police.”

Victor looked stricken at that. “Please, Mrs. L, just leave me alone.”

“But … why, Victor? You are such a nice kid, such a smart kid, why would anyone do this to your bike? Why would they beat you up?”

“You really don’t know, do you?”

Almost in tears myself (please remember, I was twenty-four at the time), I shook my head.

“They used to be my friends, but now they don’t like it that I do well in school. They keep saying I decided to ‘go white’.”

“‘Go white’? I don’t understand.”

“In my neighborhood, in my family, we don’t take honors classes and get straight As and awards from principals. We stick together. We don’t try to be better than what we are.”

“But … you’re a straight A student in Honors classes. You can do anything you want, Victor.”

“I know,” he said with a sunny smile. “That’s why I don’t let this stuff bother me.”

The next day, Victor was not in school. He had been badly beaten for talking to a white teacher outside of school. He came back to school a few days later, determined as ever to break the mold. I left the district to take a job closer to home, but I remember thinking that Victor would be okay; he would be a success story.

I returned to that district at the high school level two years later, missing the size and the diversity and the unique challenges that I loved working with.

I saw Victor once, in a crowd of students in the same minority group as he. He saw me, did a double take, then looked away. Confused, I went on my way. I did ask around, though. Victor was a D/F student in low level classes. He was involved in gang activities. Rumor had it he’d been in police trouble on several occasions. He was no longer “a nice kid”.

I have no idea what happened to Victor, the story that transpired in the years I worked in a different district. I do know that he changed dramatically, that he had clearly made the decision that ‘going white’ was no longer his path.

It was not the school staff that did this to Victor, nor was it necessarily his family. Victor had, somewhere along the way, lost the strength to stand up to his peer group. He had accepted his peer-defined identity of who he should be as a minority, and that identity did not value Honors or AP classes, never mind school itself.

Nobody wants to talk about the power of peers when it comes to minority groups possessing an “Us versus Them” paradigm, but that is the very base of it. I say that from fifteen years in education.

It is the elephant that nobody wants to name because we fear being labeled racist even as we squawk about being colorblind.

I take each child that I am given the privilege to teach, and I work with them from where they are at on what they are able and willing to give and receive. I truly believe that most teachers do the same.

So why am I writing this today?

The city I live in is in upheaval over student representatives being added to an ad-hoc school board committee tasked with exploring ways to include student voice on the school board. Each high school principal was asked to choose a representative from their school. The principals, I’m sure, worked hard to ensure that these representatives were not white, Harvard-bound males. It is a diverse city, and ignoring that diversity would be wrong. Principals know their student body, and they know the student that would best represent its unique voice.

What has happened is that a group focused on community organizing, a group made up of exclusively of minority students, a group that has made derogatory and false statements about their schools, a group that has misrepresented adult leaders as students to the press, has pushed their way into the ad hoc group made up of the principal-selected representatives.

Among other things, this group has been vocal about minorities being discouraged from (or even forbidden from) taking upper level classes. They blame the schools. They blame the teachers. They blame the school board.

Victor was the most extreme case I’ve seen, but based on my experience as a teacher it is the peer groups that want to keep anyone from defecting, from ‘going white’. The opportunities are there, for minorities and for all students, if they are willing and able to work to achieve them. They are encouraged by teachers. In fact, teachers and school administration would love it if their upper level classes were a perfect balance of diversity. What a feather in the school district’s cap that would be!

But teachers and citizens that are not of this minority group do not want to say anything. They don’t want to name the elephant because “Racist” or “Sexist” or “Prejudiced” is not a label anyone wants to wear. It would be all too easy to dismiss anyone who tries to raise this issue with one of those labels without ever addressing the issue itself.

And that group? They do not want to talk about the elephant in the room either, but perhaps they should if they truly want to engage in a dialogue that leads to understanding.